What Is Portal Vein Thrombosis?

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) happens when a blood clot blocks the portal vein - the main vessel that carries blood from your intestines to your liver. It’s not rare, especially in people with liver disease, cancer, or inherited clotting disorders. The clot can be partial or complete, and it can show up suddenly (acute) or develop slowly (chronic). Acute PVT is more treatable. If left alone, it can lead to serious problems like intestinal damage, worsening liver scarring, or even make someone ineligible for a liver transplant.

Why Diagnosis Matters - And How It’s Done

Many people with PVT don’t feel anything at first. That’s why it’s often found by accident during imaging for something else, like an ultrasound for abdominal pain or a liver scan before a transplant evaluation. The first and most reliable test is a Doppler ultrasound. It’s non-invasive, widely available, and picks up the clot in 89-94% of cases. What the scan looks for: is the vein filled with blood? Is there a clot? Are there abnormal side vessels forming - a sign called cavernous transformation?

Doctors classify the clot by how much it blocks the vein: less than 50% is minimally occlusive, 50-99% is partial, and 100% is complete. If the original vein disappears and is replaced by a network of tiny vessels, that’s chronic PVT. CT or MRI scans are used if the ultrasound is unclear or if there’s suspicion of cancer or other complications.

When Anticoagulation Is the Right Move

For years, doctors were unsure whether to use blood thinners in PVT, especially if the patient had cirrhosis. The fear was bleeding. But research over the last five years has changed everything. Now, major liver societies - the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) - agree: anticoagulation is the standard of care for most acute PVT cases, even in cirrhosis, if the patient isn’t actively bleeding.

The goal isn’t just to prevent the clot from growing. It’s to dissolve it. Studies show that if you start anticoagulation within six months of diagnosis, 65-75% of patients get full or partial reopening of the portal vein. If you wait longer, that number drops to 16-35%. That’s a huge difference in long-term survival.

Which Blood Thinners Work Best?

Not all anticoagulants are the same for PVT. The choice depends on whether you have cirrhosis, how bad your liver function is, and your risk of bleeding.

- Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) - Like enoxaparin - is often the first choice, especially for cirrhotic patients. It’s given as a daily injection, doesn’t need frequent blood tests, and has more predictable results in liver disease. Dosing is based on weight: 1 mg/kg twice daily or 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

- Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) - Rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran - are now preferred for non-cirrhotic patients. They’re pills, easier to take, and studies show better recanalization rates: 65-75% compared to 40-50% with warfarin. Rivaroxaban 20 mg daily and apixaban 5 mg twice daily are the most studied doses.

- Warfarin (VKAs) - Still used, especially where DOACs aren’t available. But it requires frequent INR checks (target 2.0-3.0) and interacts with food and other meds. It’s less effective than DOACs in non-cirrhotic patients.

In cirrhotic patients with Child-Pugh A or B, LMWH still leads in safety and results. DOACs are now approved for Child-Pugh B7 patients as of early 2024, based on new trial data showing results just as good as LMWH.

Who Should NOT Get Anticoagulation?

Anticoagulation isn’t for everyone. It’s avoided if:

- You’ve had a recent variceal bleed (within the last 30 days)

- You have uncontrolled ascites or severe fluid buildup

- Your liver function is Child-Pugh class C - meaning advanced, decompensated cirrhosis

In these cases, the risk of life-threatening bleeding - especially from esophageal varices - outweighs the benefit. For cirrhotic patients with PVT, doctors now recommend an endoscopy to check for varices before starting blood thinners. If varices are found, they’re treated with band ligation first. One study showed this cut major bleeding from 15% down to 4%.

How Long Do You Need to Take Blood Thinners?

It’s not a one-size-fits-all answer.

- Provoked PVT - If the clot was caused by something temporary like recent surgery, infection, or a central line - treatment lasts at least 6 months. After that, if the trigger is gone and the vein is open, you may stop.

- Unprovoked PVT - If no clear cause is found, especially in non-cirrhotic patients, you’re likely to have an inherited clotting disorder. About 25-30% of these patients have mutations like Factor V Leiden. For them, lifelong anticoagulation is usually recommended.

- PVT with cancer - If the clot is linked to an active tumor, anticoagulation continues as long as the cancer is active. LMWH is often preferred here, too.

Rechecking the clot with ultrasound after 3-6 months of treatment is standard. If the vein is still blocked, treatment continues. If it’s open and you’re stable, your doctor will talk about stopping or continuing.

What About Surgery or Other Treatments?

Anticoagulation is the first line - but not the only option.

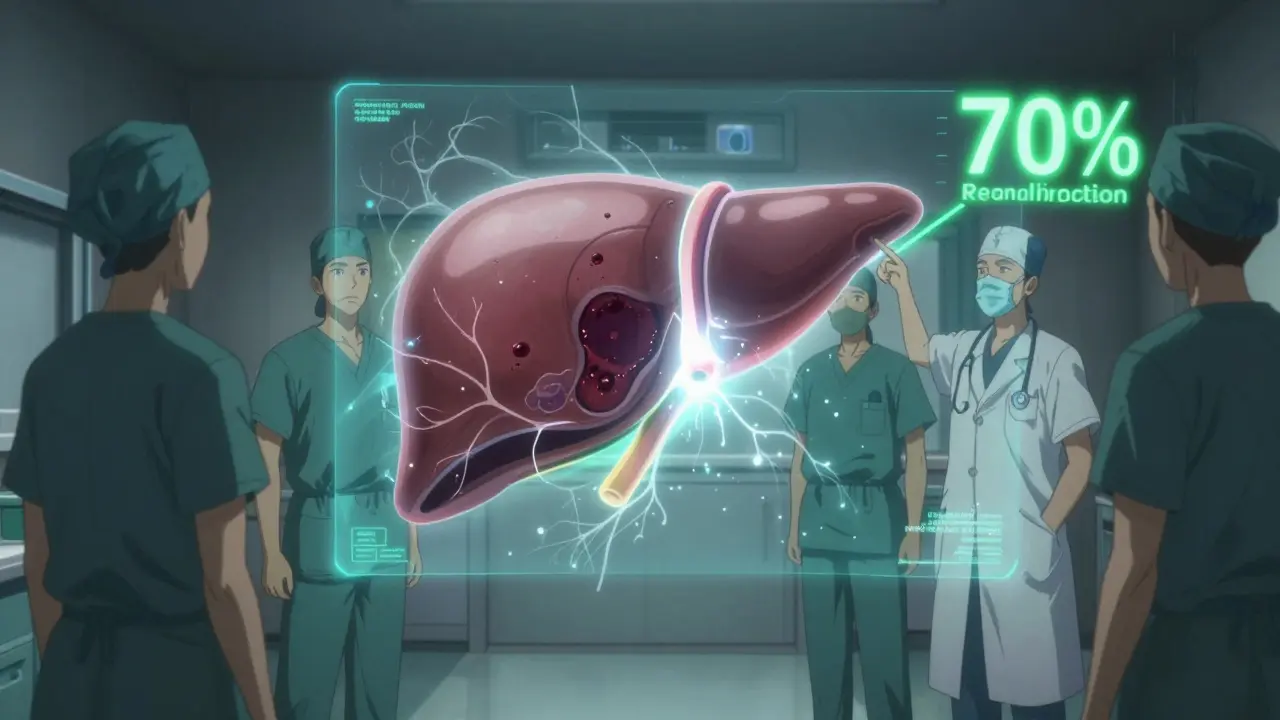

- TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) - A metal tube placed inside the liver to reroute blood flow. Used when anticoagulation fails or if portal hypertension is causing dangerous pressure. Success rates are 70-80%, but 15-25% of patients develop hepatic encephalopathy - brain fog from liver toxins.

- Thrombectomy - A catheter is inserted to physically break up the clot. Works well (60-75% success) but only available in big medical centers. Usually reserved for acute, severe cases with signs of intestinal ischemia.

- Liver transplant - PVT used to be a reason to deny transplant listing. Now, anticoagulation before transplant improves survival. One study showed 85% of anticoagulated patients survived one year after transplant, versus 65% without it.

Most patients never need surgery. Anticoagulation alone works well enough in the majority.

Real-World Challenges and Tips

Managing PVT isn’t simple. Even in top hospitals, mistakes happen.

- Delayed diagnosis - If PVT isn’t caught early, mortality jumps. At Massachusetts General, 22% of patients who presented with intestinal ischemia died. Only 5% died if treated promptly.

- Low platelets - Many cirrhotic patients have low platelet counts. Some centers safely start anticoagulation with platelet transfusions to keep counts above 30,000/μL.

- Coordination matters - The best outcomes happen when hepatologists, radiologists, and transplant teams work together. Johns Hopkins found a 35% drop in complications with a structured team approach.

- Community gaps - Only 35% of general gastroenterologists feel confident managing PVT anticoagulation. If you’re not in a big center, ask for a liver specialist consult.

What’s New in 2025?

The field is moving fast. In January 2024, the AASLD updated its guidelines to allow DOACs in Child-Pugh B7 patients - a big shift. Andexanet alfa, a new reversal agent for rivaroxaban and apixaban, gives doctors a safety net if bleeding happens. A major trial comparing rivaroxaban to enoxaparin in cirrhotic patients is underway, with results expected in late 2025. Meanwhile, a new drug called abelacimab is being tested in phase 2 trials for PVT.

Genetic testing is also becoming more common. If you have Factor V Leiden or the prothrombin gene mutation, your chance of recanalization with long-term anticoagulation is 80% higher. That’s changing how we think about treatment duration.

Final Takeaway

Portal vein thrombosis isn’t a death sentence. With early diagnosis and proper anticoagulation, most people can avoid serious complications, restore blood flow to the liver, and live normally. The key is acting fast, choosing the right blood thinner for your liver condition, and avoiding bleeding risks. If you’ve been diagnosed with PVT, don’t delay treatment. Talk to your doctor about getting started - and make sure you’re seeing someone who knows the latest guidelines. Your liver depends on it.

Can portal vein thrombosis go away on its own?

Sometimes, especially if the clot is small and caused by a temporary issue like an infection or recent surgery. But it’s unpredictable. Without treatment, the clot can grow, block more blood flow, or turn chronic. Anticoagulation increases the chance of complete recanalization from under 20% to over 65%. Waiting is risky.

Is anticoagulation safe if I have cirrhosis?

Yes - if your cirrhosis is compensated (Child-Pugh A or B) and you don’t have active bleeding or uncontrolled ascites. LMWH is often preferred because it’s more predictable. DOACs are now approved for Child-Pugh B7 patients as of early 2024. The biggest risk is bleeding from varices, which is why endoscopic screening and banding before starting anticoagulation is now standard.

Do I need lifelong blood thinners for PVT?

Only if you have an inherited clotting disorder (like Factor V Leiden) or active cancer. For most people with a clear trigger - like recent surgery or infection - 6 months of treatment is enough, especially if the vein reopens. Your doctor will repeat imaging to check. If the clot is gone and no risk factors remain, you may stop safely.

Can I take DOACs like rivaroxaban if I have liver disease?

DOACs are safe for mild to moderate liver disease (Child-Pugh A or B7). They’re not recommended for severe cirrhosis (Child-Pugh C) due to higher bleeding risk and altered drug metabolism. Rivaroxaban and apixaban are the most studied. Always check kidney function too - DOACs are cleared through the kidneys, so dosage may need adjustment.

What happens if I don’t treat portal vein thrombosis?

Untreated PVT can lead to worsening portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, intestinal ischemia (tissue death in the bowel), and liver failure. It can also make you ineligible for a liver transplant. Five-year survival drops to under 40% without treatment, compared to 85% with early anticoagulation. The risk isn’t just long-term - it’s immediate.

How do I know if the clot is dissolving?

Your doctor will order a follow-up Doppler ultrasound after 3-6 months of anticoagulation. They’ll look to see if the portal vein is visible again, if blood flow has returned, and if the clot has shrunk or disappeared. Partial or complete recanalization means treatment is working. No change means the treatment may need adjustment.

Next Steps If You’re Diagnosed

Here’s what to do right away:

- Confirm the diagnosis with a Doppler ultrasound - don’t rely on a single scan if it’s unclear.

- Get liver function tested - Child-Pugh and MELD scores help determine your risk.

- Have an endoscopy to check for varices - if found, get them treated before starting blood thinners.

- Ask for a thrombophilia workup - especially if you’re under 50 and have no clear cause.

- Start anticoagulation within 30 days if you’re a candidate - delay reduces success rates dramatically.

- Work with a hepatologist or liver transplant center - they’re most familiar with current protocols.

Portal vein thrombosis is serious - but treatable. The tools to fix it exist. What matters most is acting quickly and following the right path based on your liver health.

Comments (9)

Nishant Garg

January 16, 2026 AT 02:36 AMHonestly, this is one of those posts that makes you realize how much we take liver health for granted. I'm from India, and in our rural areas, people don't even know what the portal vein is. I've seen patients with cirrhosis get diagnosed with PVT only after they start vomiting blood. The fact that anticoagulation can reverse this in 70% of cases if caught early? That's not just medicine-it's a miracle. LMWH might be a pain to inject, but it's worth every prick. And DOACs for Child-Pugh B7? Finally, someone caught up with reality. Let's get this info out to every small-town clinic.

Nilesh Khedekar

January 17, 2026 AT 00:40 AMOhhhhh, so NOW we're giving blood thinners to cirrhotics??? After decades of telling them 'NO, you'll bleed out'??? And now suddenly it's 'safe'??? Who approved this? Was there a secret meeting in Geneva? Or did Big Pharma just whisper sweet nothings into AASLD's ears? I've seen patients on rivaroxaban bleed from their gums just from brushing their teeth. This is not progress-it's a gamble with human lives. And don't even get me started on the 'endoscopy first' nonsense-half the hospitals here can't even find a vein to draw blood from!

Jami Reynolds

January 18, 2026 AT 17:57 PMI find it deeply concerning that guidelines are being updated based on 'new trial data' without sufficient long-term outcome studies. The use of DOACs in patients with hepatic impairment raises serious pharmacokinetic concerns-especially since the liver metabolizes these drugs. The FDA has not yet approved rivaroxaban for Child-Pugh B7 patients. This appears to be a case of guideline creep, driven more by commercial interests than clinical evidence. The risk of intracranial hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients is not trivial. We are playing Russian roulette with organ failure.

Niki Van den Bossche

January 18, 2026 AT 23:41 PMThere's something profoundly existential about clotting in the portal vein-it's not just a vascular event, it's a metaphysical rupture in the body's symbiotic relationship with digestion. The liver, that ancient alchemist, suddenly severed from its nourishing river. Anticoagulation becomes less a medical intervention and more a cosmic negotiation: do we dare disturb the natural order of stagnation? And yet... the data shows recanalization. So perhaps the body, in its quiet wisdom, whispers: 'Let flow return.' The real tragedy isn't the clot-it's the silence of systems that delay diagnosis until the vessel is a ghost of itself.

Jan Hess

January 19, 2026 AT 16:13 PMThis is exactly the kind of info we need more of. I'm a nurse in a community hospital and I used to panic when PVT came up. Now I know: if the patient isn't actively bleeding and their platelets are above 30k, we can start LMWH and refer them ASAP. I showed this to my team and we made a one-pager for our GI docs. We even printed it and put it in the ultrasound room. Small wins. Let's keep pushing this out to primary care. People are dying because no one connects the dots. You don't need a transplant center to save a life-you just need to know what to look for.

Diane Hendriks

January 21, 2026 AT 06:10 AMThe notion that anticoagulation can be safely administered to patients with cirrhosis without standardized, nationwide protocols is not only reckless-it is an affront to medical ethics. The United States lacks uniform guidelines for thrombophilia screening in PVT. The reliance on regional expertise creates dangerous disparities. Furthermore, the promotion of DOACs over LMWH in resource-limited settings is economically predatory. This is not medicine. This is market-driven healthcare masquerading as science.

Frank Geurts

January 21, 2026 AT 08:45 AMI must express my profound appreciation for the rigor and clarity of this exposition. The integration of contemporary guidelines from AASLD and EASL, coupled with the nuanced differentiation between provoked and unprovoked PVT, represents a paradigm shift in hepatology. The emphasis on endoscopic prophylaxis prior to anticoagulation is particularly commendable; it reflects a holistic, multidisciplinary approach that prioritizes patient safety above all else. One cannot overstate the importance of coordinated care between hepatologists, radiologists, and transplant teams. This is the gold standard-elegantly articulated and impeccably evidence-based.

Annie Choi

January 23, 2026 AT 07:00 AMTIPS success rates are solid but hepatic encephalopathy is a silent killer. We're seeing more patients with grade 2-3 HE post-TIPS and no one talks about it. Also-DOACs in Child-Pugh B7? The renal clearance data is still shaky. We need more real-world data on CrCl <30. I've seen three patients on apixaban crash with AKI after starting. Just saying: don't skip the labs.

Arjun Seth

January 23, 2026 AT 07:29 AMYou people are insane. This isn't medicine, it's gambling. If your liver is bad, you shouldn't be on blood thinners. Period. My uncle had cirrhosis and took warfarin-he bled out in three days. The doctors said 'it was his time.' No. It was their arrogance. Stop pretending science is magic. Sometimes the body knows better than your algorithms. Don't fix what isn't broken. Let nature take its course.