When you walk into a pharmacy to pick up your prescription, you probably don’t think about how much the pharmacy gets paid for it. But behind the counter, there’s a complex financial system at work-one that determines whether you get the cheapest version of your medicine, or a more expensive one that doesn’t actually work better. This system is called pharmacy reimbursement, and it’s shaped by how pharmacies are paid for generic drugs. The way this works has real consequences: it affects what drugs are stocked, how much pharmacies make, and even whether you can afford your meds.

How Generic Substitution Works (And Why It Matters)

Generic drugs are copies of brand-name medications. They contain the same active ingredients, work the same way, and are just as safe. But they cost a fraction of the price. In 1993, only about one-third of prescriptions filled were for generics. By 2023, that number jumped to over 90%. That’s not because doctors suddenly changed their minds-it’s because the system started paying pharmacies more to dispense them. The idea behind generic substitution is simple: swap out a pricey brand-name drug for a cheaper generic. The savings should flow to patients, insurers, and taxpayers. But in practice, the money doesn’t always go where it should. Why? Because reimbursement models don’t always reward the lowest-cost option.How Pharmacies Get Paid: The Three Key Pieces

Pharmacy reimbursement isn’t one flat rate. It’s made up of three parts:- Ingredient cost-what the pharmacy pays the wholesaler for the drug

- Dispensing fee-a flat payment for the labor of filling the prescription

- Reimbursement method-how the total payment is calculated

The Spread Pricing Problem

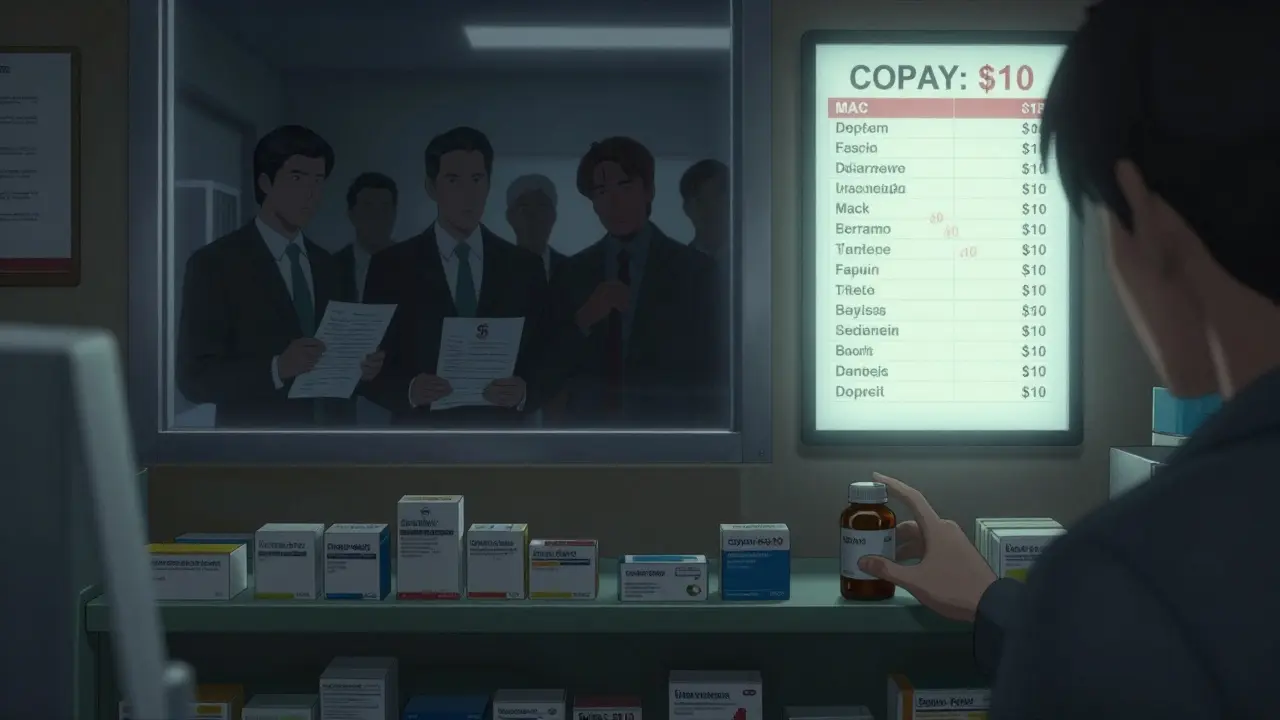

This is where things get shady. Many Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)-the middlemen between insurers and pharmacies-use a trick called spread pricing. Here’s how it works:- The PBM negotiates a low acquisition price from the pharmacy (say, $1.20 per pill)

- The PBM tells the insurer or Medicare it will reimburse $6.00 per pill

- The patient pays a $10 copay

- The pharmacy gets $6.00, even though they paid $1.20

- The PBM pockets the $4.80 difference-the “spread”

Why Cost-Plus Reimbursement Isn’t the Fix

Some experts suggest switching to cost-plus reimbursement-where pharmacies get paid a fixed percentage above what they paid for the drug, plus a dispensing fee. It sounds fair. But it has a dark side. If a pharmacy buys a generic for $1.50 and the reimbursement is set at 15% above cost plus $4.50 dispensing fee, they make $6.23. But if the next generic in line costs $0.80, they only make $5.62. That’s less profit. So the pharmacy might not push the cheaper option. They might even avoid stocking it. This isn’t theoretical. In states that tried cost-plus models, independent pharmacies reported reduced margins and began cutting back on generic inventory. The result? Patients had fewer options. Some had to switch pharmacies. Others had to wait days for a drug to be ordered.The Real Savings Are in Therapeutic Substitution

Most people think generic substitution means swapping one pill for another identical one. But the biggest savings come from therapeutic substitution-switching from a brand-name drug to a completely different generic drug in the same class. For example, instead of prescribing a $150 brand-name blood pressure pill, a doctor could prescribe a $3 generic that works just as well. In 2007, switching just seven classes of brand-name drugs to generics saved Medicare $4 billion. Substituting one generic for another? That only saved $900 million. But PBMs rarely incentivize therapeutic substitution. Their MAC lists often don’t include the cheapest therapeutic alternative. Why? Because if you only pay for the cheapest version, you don’t get the spread. And if you don’t get the spread, you don’t make money.What’s Happening to Independent Pharmacies?

Over 3,000 independent pharmacies shut down between 2018 and 2022. Why? Because they can’t survive on today’s reimbursement rates. PBMs control about 80% of prescription claims through just three companies: CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx. These giants set the rules. They decide which drugs are on MAC lists. They decide how much pharmacies get paid. And they often contract with pharmacies on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. Independent pharmacies don’t have the leverage to negotiate. They’re stuck with low margins on generics-sometimes as low as 3% profit. Meanwhile, brand-name drugs give them 3.5% margins. So some pharmacies end up preferring to sell expensive drugs, even when generics are available. It’s not because they’re greedy. It’s because they’re trying to stay open.

Regulators Are Starting to Push Back

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) launched investigations into PBM spread pricing in 2023. They’re asking: Why aren’t MAC lists transparent? Why do some generics cost 20 times more than others? Why do patients pay more even when cheaper options exist? The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 forced Medicare Part D to disclose pricing. Now, pressure is building to extend that to commercial plans. Fifteen states have created Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) that set Upper Payment Limits (UPLs)-essentially, a cap on how much insurers can be charged for a drug. These UPLs are working. In states like Maryland and Vermont, generic drug prices dropped by 15-30% after UPLs were implemented. But there’s a trade-off. Some pharmacies stopped carrying high-cost specialty drugs because they couldn’t make enough to cover storage and handling.What Does This Mean for You?

If you’re on a generic drug and your copay went up this year, it’s not because the drug got more expensive. It’s because the reimbursement system changed. Your pharmacy might have been forced to switch to a more expensive generic just to stay in business. If you’re paying $10 for a pill that costs $1.50 to make, you’re not saving money. The system is. The solution isn’t to stop using generics. It’s to fix how they’re paid for. We need reimbursement models that reward the lowest-cost option, not the highest-margin one. We need MAC lists that are public, updated weekly, and based on real market prices-not what PBMs want to charge. And we need pharmacies to be able to make enough to stay open. Because if they close, you lose access. Even to the cheapest drugs.What’s Next?

The next five years will decide whether pharmacy reimbursement becomes more transparent-or more opaque. PBMs will keep pushing for higher margins. Pharmacies will keep fighting to survive. And patients? We’ll keep paying the difference. The good news? Awareness is growing. More states are passing transparency laws. More patients are asking pharmacists: “Why is this generic so expensive?” That question is the first step toward real change.Why do some generic drugs cost more than others?

Not all generics are the same. Two drugs with the same active ingredient can have different prices because they’re made by different manufacturers, come in different forms (like extended-release vs. immediate-release), or are listed under different MAC tiers. PBMs often favor higher-priced generics because they can charge insurers more and keep the difference as profit-this is called spread pricing. The pharmacy doesn’t control this; the PBM does.

Do pharmacies make more money on brand-name drugs or generics?

On paper, pharmacies make far more profit on generics-around 42.7% gross margin-compared to just 3.5% on brand-name drugs. But that’s only true if the reimbursement system allows it. In reality, many pharmacies earn less on generics because reimbursement rates are artificially low. Some even lose money on generics and rely on brand-name sales or other services to stay afloat.

Can I ask my pharmacist to switch to a cheaper generic?

Yes. Pharmacists are trained to identify therapeutic alternatives and can often suggest a cheaper option that’s covered under your plan. But they’re limited by what’s on the PBM’s MAC list. If the cheapest option isn’t approved, they can’t dispense it-even if it’s safe and effective. Always ask: “Is there a lower-cost generic available?”

Why don’t insurance plans always cover the cheapest generic?

Insurance plans rely on PBMs to manage drug lists. PBMs often choose higher-priced generics because they profit from the price gap between what they pay the pharmacy and what they charge the plan. Even if a cheaper drug exists, it may not be on the formulary. This isn’t about effectiveness-it’s about profit.

How do state laws affect generic substitution?

Some states require pharmacists to substitute generics unless the doctor says no. Others allow substitution only if the patient agrees. But even in states with strong substitution laws, reimbursement rules can block savings. If the PBM pays too little for the cheapest generic, the pharmacy may refuse to stock it. So the law works-but only if the money follows.

Comments (14)

Justin Fauth

February 4, 2026 AT 17:33 PMLet me tell you something-this whole system is rigged. PBMs are just middlemen sucking the life out of pharmacies and patients alike. I run a small pharmacy in Ohio, and we’re barely breaking even on generics. Meanwhile, CVS Caremark is making bank on the same pills we’re forced to sell at a loss. It’s not about health-it’s about profit. And don’t get me started on how they pick which generics to cover. It’s pure greed wrapped in a white coat.

Joy Johnston

February 5, 2026 AT 01:35 AMAs a pharmacist with 18 years in the field, I can confirm every point in this post. The MAC lists are a joke-unpredictable, outdated, and manipulated. I’ve had patients come in asking why their $1.20 generic cost them $15, and I had to explain that the PBM pocketed the difference. We’re not greedy. We’re just trying to keep our doors open. Transparency isn’t a luxury-it’s a necessity. If we want real savings, we need public, real-time pricing data. No more black boxes.

Janice Williams

February 6, 2026 AT 18:43 PMOne must, with utmost seriousness, consider the underlying economic fallacies embedded within this narrative. The assumption that reimbursement should incentivize the lowest-cost option is fundamentally flawed. Market dynamics, not moral imperatives, determine value. Furthermore, the notion that pharmacies are 'forced' to prioritize expensive generics ignores the complexity of supply chain logistics and contractual obligations. One cannot simply legislate away market inefficiencies with emotional appeals.

Meenal Khurana

February 7, 2026 AT 03:27 AMSimple truth: if the pharmacy can't make money on a generic, they won't stock it. Patients lose. End of story.

Zachary French

February 8, 2026 AT 01:38 AMOhhhhh boy. Where do I even BEGIN? This whole thing is a MASTERCLASS in corporate corruption. PBMs are the VAMPIRES of the healthcare system-sucking blood from pharmacies, patients, and even Medicare itself. And let’s be real: if you think the 'cost-plus' model is the fix, you’re dreaming in technicolor. It’s like trying to plug a dam with a toothpick. The system is BROKEN. And no, I don’t have a degree-but I read the news. And I know a scam when I see one.

Amit Jain

February 8, 2026 AT 09:06 AMIn India, generic drugs are cheap because we don’t have PBMs. Manufacturers sell directly to pharmacies. No middleman. No spread. No drama. Simple. Why can’t US do same? Why need 3 companies control everything? Just remove middlemen. Problem solved.

Daz Leonheart

February 8, 2026 AT 11:55 AMYou’re not alone out there. I’ve seen too many independent pharmacies close up shop over the last five years. It breaks my heart. But here’s the thing-we can fix this. It’s not about blaming pharmacists or patients. It’s about policy. We need public MAC lists. We need caps on spreads. We need to stop letting corporations decide what medicine people can get. It’s not rocket science. It’s just common decency.

Kunal Kaushik

February 8, 2026 AT 18:22 PMMan… this hits hard. 😔 I’ve had my mom’s blood pressure med go from $4 to $18 in a year. She asked the pharmacist why. He just sighed and said, 'It’s not up to me.' That’s the real tragedy-not the price, but the helplessness. We need to change this. For real.

Alec Stewart Stewart

February 10, 2026 AT 15:35 PMThank you for writing this. I’ve been silent for too long. I work at a rural pharmacy, and every day I watch people choose between their meds and groceries. We’re not just selling pills-we’re selling dignity. If we don’t fix reimbursement, we’re not just losing pharmacies-we’re losing trust. And that’s harder to rebuild than any balance sheet.

Demetria Morris

February 12, 2026 AT 04:28 AMIt’s clear that greed has taken over healthcare. People who can’t afford their prescriptions are being punished for being poor. And yet, no one in power seems to care. The fact that PBMs profit from the suffering of the sick is not just unethical-it’s a moral failure of civilization. We must hold them accountable. Not tomorrow. Not next year. Now.

Prajwal Manjunath Shanthappa

February 13, 2026 AT 19:33 PMOne must acknowledge, with due deference to the scholarly rigor of the preceding exposition, that the structural inequities inherent in the current PBM-dominated reimbursement paradigm constitute a veritable oligarchic encroachment upon the sanctity of pharmaceutical accessibility. The conflation of therapeutic equivalence with economic expediency represents not merely a market failure, but a epistemological collapse of medical ethics. One is compelled to interrogate: Is profit, in this context, not the ultimate pathology?

Mandy Vodak-Marotta

February 13, 2026 AT 20:31 PMOkay, I’ve been reading this whole thing and I just need to say-I’m 28 and on 5 prescriptions. My copay went from $10 to $35 last year. I called my pharmacy, and they told me the PBM changed the MAC list overnight. I had to switch from the $1.50 generic to the $8 one. I asked why. They said, 'We’re not allowed to give you the cheaper one.' I felt like I was being robbed. And the worst part? I’m not even angry. I’m just… tired. I’m tired of being treated like a number. I’m tired of people acting like this is normal. This isn’t healthcare. This is a casino with pills.

Keith Harris

February 15, 2026 AT 17:26 PMOh, so now we’re blaming PBMs? Please. The REAL problem is that pharmacies are incompetent. If they were better at negotiating, they wouldn’t be stuck with 3% margins. And let’s be honest-most patients don’t even know what a MAC list is. That’s their fault too. Stop whining. If you want cheaper drugs, go to Canada. Or Mexico. Or learn to shop around. This isn’t a crisis-it’s a lifestyle choice.

Jesse Naidoo

February 15, 2026 AT 19:50 PMWait, so if the pharmacy makes less on cheaper generics, they avoid stocking them? That means they’re basically choosing profit over patient care? I mean… wow. Just… wow. And you’re telling me this isn’t illegal? This is worse than the opioid crisis. At least then they were lying. Now they’re just… silent. And making money while you suffer. I’m done. I’m done with this system.