Every year, hundreds of thousands of people in the U.S. end up in the hospital because of unexpected side effects from medications they were prescribed. These aren’t mistakes in dosing or pharmacy errors-they’re adverse drug reactions (ADRs) caused by how a person’s genes process drugs. One person might take a common painkiller and feel fine, while another suffers liver damage or a dangerous skin reaction. The difference? Genetics.

Pharmacogenetic testing looks at your DNA to predict how your body will respond to certain medications. It’s not science fiction-it’s already saving lives. In 2023, a landmark study called PREPARE, involving nearly 7,000 patients across Europe, proved that testing before prescribing can cut serious drug reactions by 30%. That’s not a small number. It’s the difference between a routine visit and an ICU admission.

How Your Genes Control How Drugs Work

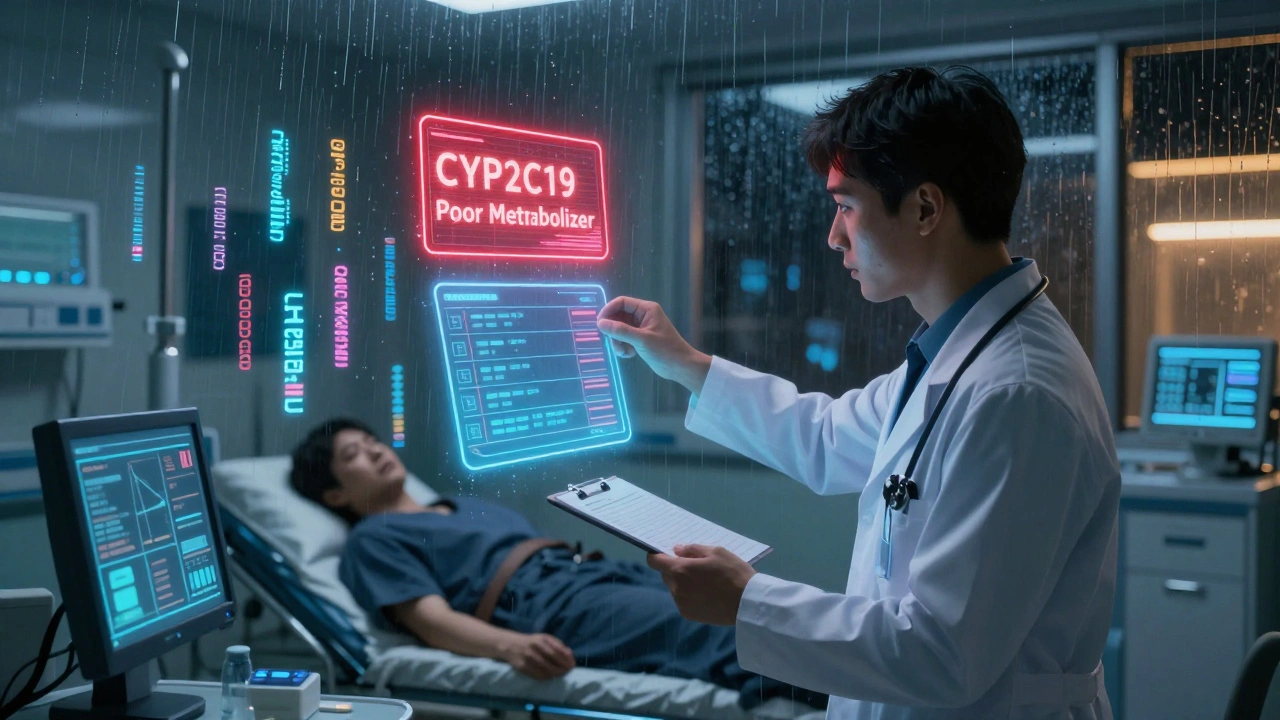

Your body doesn’t treat every drug the same way. Two people taking the same pill at the same dose can have completely different outcomes because of enzymes coded by their genes. The most important ones are in the CYP family-CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and CYP3A5. These enzymes break down more than 100 commonly used drugs, from antidepressants to blood thinners to chemotherapy.

Some people are fast metabolizers-they clear drugs too quickly, so the medicine doesn’t work. Others are slow metabolizers-they hold onto the drug too long, leading to toxic buildup. A classic example is clopidogrel, a blood thinner given after heart attacks. About 30% of people have a CYP2C19 variant that makes the drug useless. Without testing, they’re left unprotected from another heart attack.

Then there are genes like TPMT and DPYD. TPMT variants can turn azathioprine, used for autoimmune diseases, into a poison that destroys bone marrow. DPYD mutations make 5-FU, a common chemo drug, deadly for 1 in 10 patients. These aren’t rare edge cases. They’re predictable-and preventable.

The PREPARE Study: Proof It Works

The PREPARE study was the first large-scale, real-world test of preemptive pharmacogenetic testing. Researchers didn’t wait for someone to have a bad reaction. They tested patients before giving them any new meds. They used a panel of 12 genes that cover 50 key variants linked to over 100 drugs.

The results? 30% fewer serious ADRs. That’s 3 out of every 10 people who avoided hospitalization, emergency care, or permanent damage. The study didn’t just prove it works-it showed it works across different healthcare systems, languages, and populations.

What made it powerful was the integration. Test results were automatically added to electronic health records. When a doctor tried to prescribe a drug that clashed with a patient’s genes, the system popped up a warning. No one had to remember a genetic report. The tech did the work.

Which Drugs Are Most Affected?

Not every drug needs genetic testing. But for these, it’s life-changing:

- Carbamazepine (for seizures and nerve pain): People with the HLA-B*1502 gene variant-common in Asian populations-have a 95% lower risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome if tested first.

- Warfarin (blood thinner): Variants in VKORC1 and CYP2C9 affect how much you need. Testing cuts dangerous bleeding risks by 40% in the first month.

- Statins (cholesterol drugs): SLCO1B1 variants increase muscle damage risk by 4x. Testing helps avoid myopathy.

- SSRIs and SNRIs (antidepressants): CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 status tells you if you’ll need half a pill or double the dose to feel better.

- Codeine: Some people convert it to morphine too fast, causing fatal breathing problems in kids. Others don’t convert it at all-no pain relief.

The FDA now includes pharmacogenetic warnings on 329 drug labels-up from 287 just two years ago. That’s not a trend. It’s a shift in how medicine is done.

Why Isn’t Everyone Getting Tested?

If it’s this effective, why isn’t it standard? Three big reasons: cost, complexity, and knowledge gaps.

Testing costs $200-$500. That sounds expensive, but it’s cheaper than one hospital stay. The NHS estimates ADRs cost £500 million a year in avoidable admissions. A single adverse reaction can cost over $30,000. Testing pays for itself.

But money isn’t the biggest barrier. Most doctors don’t know how to interpret the results. A 2022 survey found only 37% of physicians felt confident reading pharmacogenetic reports. What’s a “poor metabolizer” vs. an “intermediate”? What do you do with a patient who has two conflicting gene variants?

That’s where tools like CPIC (Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium) come in. They publish clear, evidence-based guidelines for 34 gene-drug pairs. For example: if you’re a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer taking tamoxifen, switch to letrozole. If you’re a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer on clopidogrel, use prasugrel instead. These aren’t guesses. They’re backed by clinical trials.

Another issue? Access. Most testing is done in hospitals or specialty clinics. Primary care doctors-who prescribe the majority of drugs-rarely have access. Only 18% of primary care practices in the U.S. use pharmacogenetic testing, compared to 65% in oncology.

What About Privacy and Ethics?

People worry about their DNA being misused. Will insurers deny coverage? Will employers find out? In the U.S., GINA (Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act) protects against health insurance and employment discrimination based on genetic data. That’s strong. But it doesn’t cover life insurance or long-term care.

Still, patient acceptance is high. In studies, 85% of people say they’d take the test if their doctor recommended it. The fear isn’t about the science-it’s about misunderstanding. Clear communication helps. Explaining that the test only looks at drug metabolism genes-not cancer risk or ancestry-reduces anxiety.

What’s Next?

The future is faster, cheaper, and broader. Point-of-care tests using PCR chips are being tested in clinics. These could give results in under an hour for under $100. By 2026, that could be standard in emergency rooms and primary care offices.

Researchers are also moving beyond single genes. Polygenic risk scores combine dozens of small genetic signals to predict how someone will respond to antidepressants or pain meds. Early data shows these can improve accuracy by 40-60%.

The NIH and European Commission are pouring money into including underrepresented populations. Most genetic data comes from people of European descent. That’s a problem. A variant common in African or Indigenous populations might be missed. New studies are adding over 100 new gene-drug links from these groups.

By 2026, 87% of major U.S. academic hospitals plan to offer preemptive pharmacogenetic testing. The question isn’t if it will become routine-it’s how fast we’ll make it accessible to everyone.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for your doctor to bring it up. If you’ve had unexplained side effects from medications, or if you’re starting a new drug like an antidepressant, blood thinner, or chemo, ask:

- “Is there a genetic test that could help me avoid bad reactions?”

- “Has this drug been linked to gene variants in my ancestry group?”

- “Can we check my CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 status before starting?”

If you’ve already had a DNA test through 23andMe or Ancestry, your raw data might already include some of these variants. You can upload it to services like DNA.Land or Promethease to see if you carry any high-risk alleles. But always confirm with a clinical lab and your doctor.

Pharmacogenetic testing isn’t about predicting disease. It’s about preventing harm. It’s about making sure the next pill you take doesn’t land you in the hospital. And with the science, evidence, and infrastructure now in place, it’s no longer a luxury. It’s the next step in safe, smart medicine.

Comments (13)

Olivia Hand

December 6, 2025 AT 15:14 PMMy aunt took clopidogrel after her stent and ended up in the ER with a clot. They found out later she was a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer. If they’d tested her first, she wouldn’t have spent a week hooked to monitors, crying because she thought she was dying. This isn’t futuristic-it’s just common sense. Why are we still flying blind with prescriptions?

Sangram Lavte

December 7, 2025 AT 12:10 PMIn India, most doctors don’t even know what pharmacogenetics is. I had to explain CYP2D6 to my cardiologist last year. He looked at me like I was speaking Mandarin. We need training, not just tests. The science is here. The will isn’t.

Stacy here

December 8, 2025 AT 10:17 AMSo let me get this straight-Big Pharma doesn’t want this because if your body naturally breaks down their drug too fast or too slow, they can’t keep selling you the same pill forever? And now they’re pretending it’s about ‘cost’? Please. The FDA added 42 new genetic warnings last year. Coincidence? Or are they finally scared we’ll figure out they’ve been poisoning people on purpose for decades?

My cousin died on warfarin. They told her it was ‘unpredictable.’ Turns out she had VKORC1. They didn’t test. They didn’t care. Now they’re selling ‘precision medicine’ like it’s a new flavor of yogurt. It’s not innovation. It’s damage control.

Kyle Flores

December 8, 2025 AT 11:15 AMI’m a primary care nurse and I’ve seen this firsthand. A guy came in with rhabdomyolysis from a statin. He had the SLCO1B1 variant. His PCP had no idea. We ran the test on a whim. Turned out his whole family has it. Now his sister’s on a different statin, no issues. This isn’t just about one person-it’s about generations.

Doctors aren’t lazy. They’re overwhelmed. If the EHR just popped up a green checkmark instead of a 10-page PDF they have to read after 18 back-to-back patients, this would be standard by now. We need better tools, not more blame.

Louis Llaine

December 9, 2025 AT 04:14 AMSo you’re telling me the solution to doctors being bad at their jobs is… more DNA tests? Brilliant. Next we’ll test your blood type before giving you coffee. Maybe we should just make everyone take a quiz on pharmacogenetics before they get a prescription. Oh wait-we already have that. It’s called ‘medical school.’ And it’s broken.

Jane Quitain

December 10, 2025 AT 04:55 AMOMG this is so important!! I’ve been on 5 different antidepressants and none worked-turns out I’m a CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer. I was so depressed I thought I was broken. Turns out I just needed the right pill. This test saved my life. If you’re on meds and nothing works? ASK FOR THIS. Seriously. 💪❤️

Ernie Blevins

December 12, 2025 AT 02:31 AMIt’s all just hype. You think your genes are gonna save you? My uncle got tested, paid $400, and still got hospitalized for a reaction. The report said ‘intermediate metabolizer’-so what? The doctor didn’t change anything. This is just another way to make money off scared people.

Nancy Carlsen

December 12, 2025 AT 19:49 PMThis gave me chills. 🥹 I had no idea my codeine prescription for a toothache could’ve killed me. I’m so glad I found this. My mom’s from Mexico and we have a lot of Indigenous ancestry-do you think those variants are included in the tests? I’m gonna ask my doctor tomorrow. Thank you for writing this. 💙

Ashley Farmer

December 13, 2025 AT 15:01 PMI’m a genetic counselor, and I’ve seen how this changes lives. But the real barrier isn’t the science-it’s access. If you’re on Medicaid, or live in rural Ohio, you’re not getting tested unless you fight for it. We need to make this part of routine care, not a privilege for the well-informed. You don’t need to be a scientist to deserve safe medicine.

Sadie Nastor

December 15, 2025 AT 12:07 PMi just got my 23andme results and uploaded them to promethease… turns out i’m a cyp2c19 poor metabolizer. i’ve been on escitalopram for 3 years and it barely worked. now i’m switching to sertraline. i’m so relieved. thank you for this post. i feel less alone now 🌱

Kurt Russell

December 17, 2025 AT 07:37 AMThis isn’t just medicine-it’s justice. For decades, we’ve treated people like lab rats, guessing doses based on weight and age. But your DNA doesn’t care about your weight. It cares about your ancestry, your mutations, your biology. This is the first time we’re treating patients as individuals, not averages. And it’s long overdue. If you’re reading this and you’ve ever been told ‘it’s just how your body is’-you weren’t broken. The system was.

Kyle Oksten

December 17, 2025 AT 15:17 PMIt’s funny how we accept genetic testing for cancer but treat drug metabolism like a magic trick. If your liver can’t process a drug, that’s biology-not bad luck. We’ve known this since the 1950s with the ‘slow acetylator’ phenotype. We just chose to ignore it because it’s inconvenient. Now we’re calling it ‘precision medicine’ like it’s a new invention. It’s not. It’s just the truth finally catching up.

Helen Maples

December 19, 2025 AT 01:21 AMStop waiting for your doctor to bring it up. If you’ve ever had an unexplained reaction to a drug, get tested. It’s not expensive. It’s not scary. It’s not optional anymore. This is the future of medicine-and you don’t need permission to step into it. Ask for the test. Bring the data. Demand better. Your life depends on it.