Most people with high blood pressure never find out why. They take pills, monitor their numbers, and hope for the best. But for a small number of people-about 1 in every 200 with hypertension-the cause is a rare, hidden tumor: pheochromocytoma. It’s not just another case of essential hypertension. It’s a tumor in the adrenal gland that floods the body with adrenaline-like chemicals, turning everyday moments into life-threatening spikes in blood pressure. And unlike most high blood pressure, this one can be cured-with surgery.

What Exactly Is a Pheochromocytoma?

A pheochromocytoma is a tumor that grows in the adrenal medulla, the inner part of the adrenal glands sitting on top of each kidney. These glands normally make hormones that help your body respond to stress-like adrenaline and noradrenaline. But when a tumor forms, it doesn’t turn off. It keeps pumping out these chemicals, even when you’re sitting still, sleeping, or watching TV.

This isn’t cancer in the usual sense. About 90% of these tumors are benign-they don’t spread. But even a non-cancerous tumor can be deadly because of what it does to your blood pressure. The rest, around 10%, can become malignant and spread to other organs. That’s why catching it early matters.

These tumors are rare. Only 0.1% to 0.6% of people with high blood pressure have one. But for those who do, the symptoms are impossible to ignore once you know what to look for.

The Classic Triad: Headaches, Sweating, and Racing Heart

If you’ve ever had a panic attack, you know what it feels like-heart pounding, palms sweating, head throbbing. Now imagine that happening multiple times a day, without warning, and not because you’re scared. That’s pheochromocytoma.

The three most common symptoms-headaches, sweating, and palpitations-show up in 85% or more of patients. These aren’t mild. Headaches are often severe, throbbing, and come on suddenly. Sweating isn’t just a little dampness-it’s drenching, soaking clothes, even in cool rooms. Palpitations feel like your heart is trying to escape your chest.

Other signs include:

- Episodes of extremely high blood pressure-sometimes over 180/120 mmHg

- Pale skin during attacks

- Abdominal pain or nausea

- Unexplained weight loss

- Anxiety or panic attacks that don’t respond to therapy

These symptoms don’t happen all the time. They come in waves-called spells or paroxysms. Triggers? Physical activity, emotional stress, anesthesia during surgery, or even urinating (if the tumor is in the bladder wall, called a paraganglioma). That’s why many patients are misdiagnosed for years. Doctors think it’s anxiety, migraines, or even menopause.

Why This Tumor Causes Dangerous High Blood Pressure

Normal blood pressure stays steady. Pheochromocytoma doesn’t. The tumor releases bursts of catecholamines-epinephrine and norepinephrine-which tighten blood vessels and force the heart to beat harder and faster. That’s the body’s natural fight-or-flight response, but here, it’s happening nonstop.

What makes this worse is that the body’s ability to regulate blood pressure gets damaged over time. Many patients have something called orthostatic hypotension-meaning their blood pressure crashes when they stand up. So they might go from a blood pressure of 220/110 during an attack to 90/50 when they stand up to get a glass of water. That’s dangerous. It’s why many patients end up in the ER after fainting.

Essential hypertension-the kind most people have-doesn’t behave this way. It’s steady. It doesn’t spike and crash. It doesn’t come with sweating and palpitations. That’s the key difference. If your high blood pressure comes with those extra symptoms, you need to get tested.

How Doctors Diagnose It

There’s no single test that catches pheochromocytoma by accident. It’s found because doctors suspect it. And they suspect it when the symptoms don’t fit.

The gold standard is a 24-hour urine test for fractionated metanephrines. These are the breakdown products of adrenaline and noradrenaline. If your levels are more than three times the upper limit of normal, the chance you have a tumor is over 95%. Blood tests for plasma-free metanephrines are just as accurate and faster.

Imaging-like CT or MRI-comes after the blood or urine test. Why? Because many people have small adrenal bumps that are harmless. If you scan everyone with high blood pressure, you’ll find lots of false positives. But if your metanephrines are sky-high, then imaging tells you where the tumor is and if it’s on one or both sides.

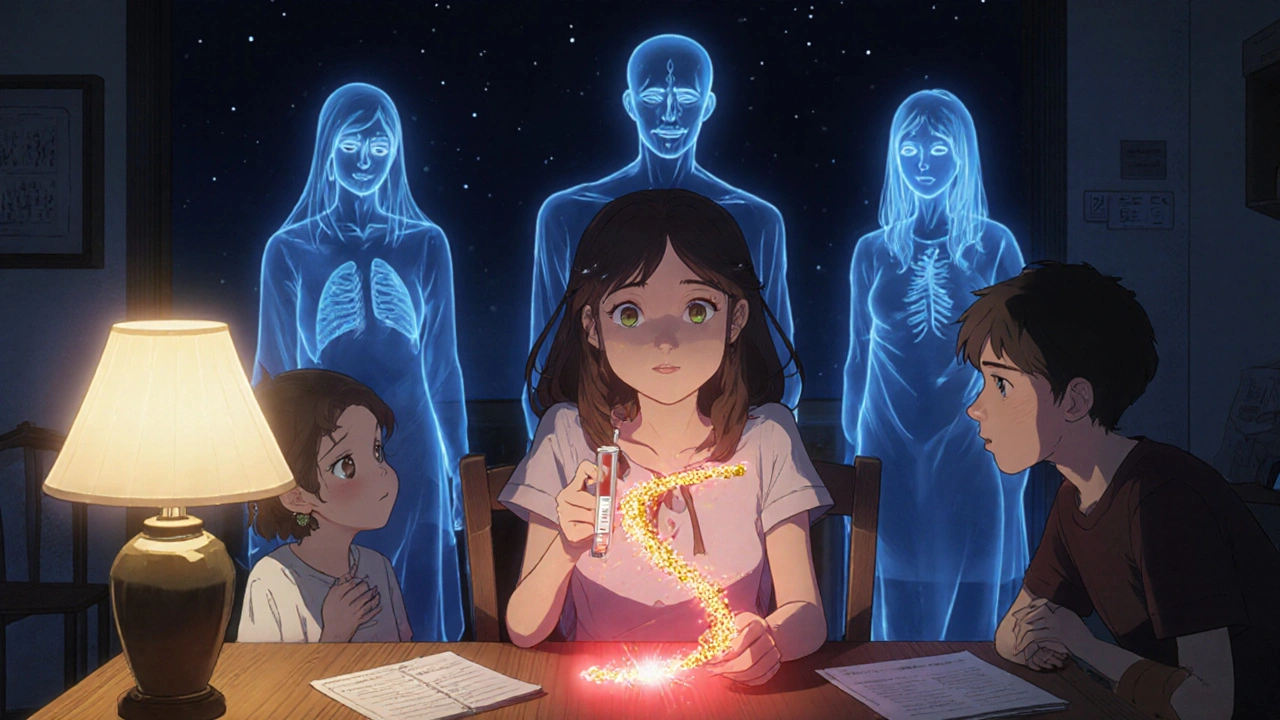

Here’s something most patients don’t know: up to 40% of pheochromocytomas are linked to inherited gene mutations. Genes like SDHB, SDHD, VHL, and RET. That’s why genetic testing is now recommended for everyone diagnosed-even if no one in their family has had it. A mutation might mean you’re at risk for other tumors, or that your children could inherit it.

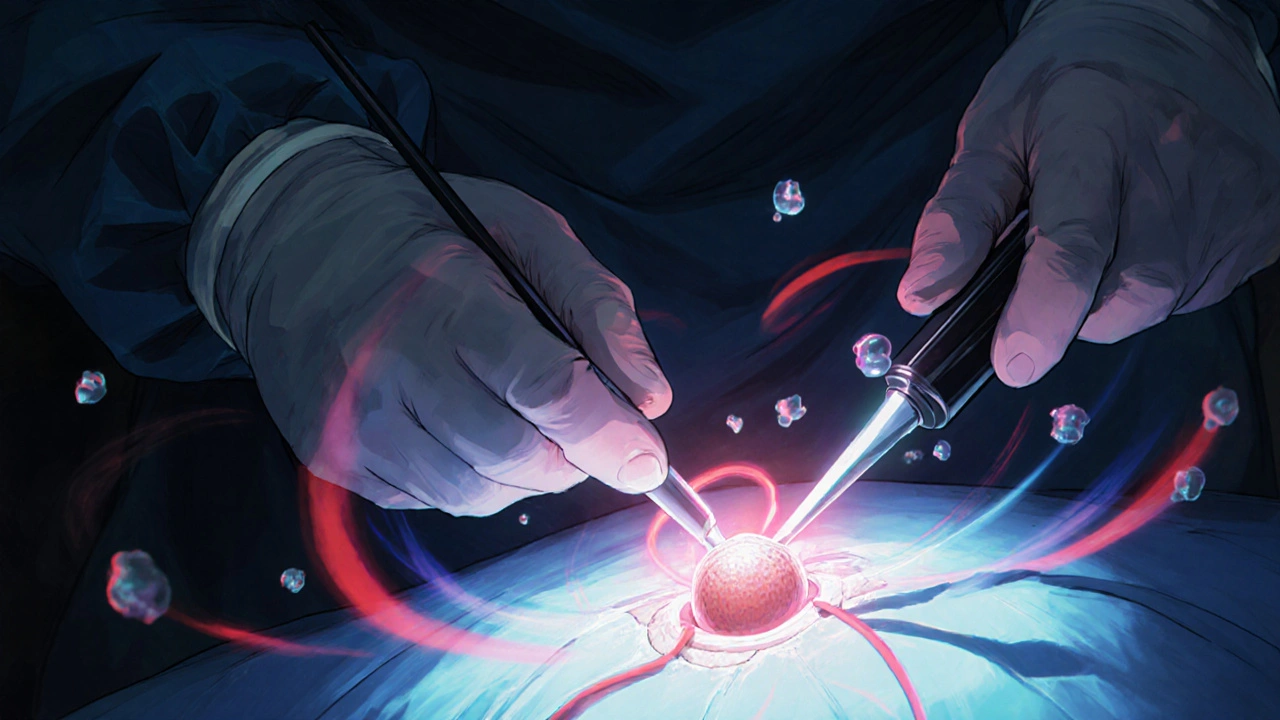

Surgery: The Only Cure

Medications can’t cure pheochromocytoma. They can only control symptoms. The only way to truly fix it is to remove the tumor. And when done right, surgery works.

Over 85% of patients see their blood pressure return to normal after the tumor is removed. Many stop all their blood pressure meds within weeks. One patient on a support forum wrote: “My BP was 210/120 for years. After surgery, it was 115/75. No pills.”

But surgery isn’t simple. You can’t just go in and pull out the tumor. Because the tumor is full of adrenaline, touching it can trigger a massive surge-causing a heart attack, stroke, or death. That’s why preparation is everything.

At least 7 to 14 days before surgery, patients start alpha-blockers like phenoxybenzamine. These drugs block the effects of adrenaline on blood vessels. Doctors also make patients drink plenty of fluids and eat a high-salt diet. Why? Because the tumor causes chronic blood vessel tightening, which shrinks the body’s blood volume. If you don’t replace that volume before surgery, your blood pressure can crash when the tumor is removed.

Most surgeries today are done laparoscopically-small incisions, camera, and tools. It’s less painful and recovery is faster. About 85% of cases use this method. But if the tumor is large or stuck to major blood vessels, the surgeon may need to switch to open surgery. That’s not a failure-it’s safety.

What Happens After Surgery

Recovery is usually quick. Most people leave the hospital in 1 to 2 days. Many are back to work in two weeks. But there are risks.

If both adrenal glands are removed-which happens in about 10% of cases-you’ll need to take steroid replacement for life: hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone. Without them, your body can’t handle stress. You could go into adrenal crisis-low blood pressure, vomiting, confusion, even death.

Even if only one gland is removed, some people feel tired for months. It’s not just physical recovery-it’s your nervous system relearning how to regulate itself without the constant adrenaline flood. About 12% of patients report chronic fatigue lasting six months or longer.

Long-term follow-up is essential. Even benign tumors can come back. Annual urine tests and imaging are recommended. And if you have an SDHB mutation, you need yearly whole-body MRIs. These tumors can grow in other places-like the chest or abdomen-and are more likely to become cancerous.

Why So Many People Are Misdiagnosed

Primary care doctors see maybe one or two cases in their entire career. Most have never treated one. So when a 35-year-old comes in with panic attacks and high blood pressure, it’s easy to say: “It’s anxiety.”

Studies show 25% of patients are initially diagnosed with anxiety disorders. One woman spent four years seeing seven doctors before her blood pressure hit 240/130 in the ER-and someone finally ordered the right test.

Another problem: borderline test results. Some people have slightly elevated metanephrines but no tumor. That’s called biochemical false positives. It happens in 15-20% of cases. That’s why doctors must match symptoms with lab results-not just treat the numbers.

There’s also a big gap in awareness. Many emergency rooms still don’t test for pheochromocytoma when someone comes in with unexplained hypertension and sweating. That’s changing, slowly. But if you’ve had these symptoms for years and nothing’s helped, ask your doctor about it.

What’s New in Treatment

For the 10% with malignant tumors that spread, surgery isn’t enough. New treatments are emerging. One is PRRT-peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. It uses radioactive particles to target tumor cells. Early results show a 65% response rate.

Another promising drug is Belzutifan, originally developed for kidney cancer in people with VHL syndrome. It’s now being tested for pheochromocytoma linked to that same gene. Early trials show it can shrink tumors without surgery.

Imaging is also getting better. Gallium-68 DOTATATE PET/CT scans are now more accurate than traditional CT or MRI-catching tiny tumors that older scans miss. This helps surgeons plan better and find hidden tumors before they grow.

When to Suspect It

You don’t need to be a doctor to ask the right question. If you have high blood pressure AND any of these, talk to your doctor about pheochromocytoma:

- Episodic headaches, sweating, and heart racing

- High blood pressure that doesn’t respond to three or more medications

- Family history of adrenal tumors, kidney cancer, or neurofibromatosis

- Unexplained weight loss with high blood pressure

- High blood pressure during pregnancy

- Episodes triggered by anesthesia, stress, or urination

It’s not common. But it’s curable. And if you’re one of the people who’ve been told it’s all in your head-ask for the test. One simple urine or blood test could change your life.

Can pheochromocytoma be cured without surgery?

No. Medications like alpha-blockers can control symptoms and lower blood pressure, but they don’t remove the tumor. Only surgical removal offers a cure. In fact, 85-90% of patients see their high blood pressure resolve completely after surgery. Without removing the tumor, the risk of sudden, life-threatening spikes remains.

Is pheochromocytoma always cancerous?

No. About 90% of pheochromocytomas are benign and do not spread. The remaining 10% have malignant potential, but even then, it’s hard to confirm cancer until the tumor spreads to other organs like the liver, bones, or lymph nodes. Genetic testing helps identify those at higher risk, especially with SDHB mutations.

Can pheochromocytoma come back after surgery?

Yes, though it’s uncommon. Recurrence happens in about 5-10% of cases, usually within the first five years. That’s why lifelong follow-up is needed-even if the tumor was benign. Regular urine tests and imaging help catch any new growth early. People with inherited mutations like SDHB have a higher risk of recurrence or new tumors elsewhere.

Why do I need to take so many pills before surgery?

The tumor releases adrenaline, which tightens your blood vessels and reduces your blood volume. Without treatment, surgery could trigger a deadly surge in blood pressure. Alpha-blockers like phenoxybenzamine relax those vessels. Adding salt and fluids helps restore your blood volume. Skipping this step is dangerous-up to 50% of patients could die during surgery without proper preparation.

What if both adrenal glands are removed?

If both glands are removed, your body can no longer make cortisol or aldosterone. You’ll need to take lifelong steroid replacement: hydrocortisone (15-25mg daily) and fludrocortisone (0.05-0.2mg daily). Missing doses can lead to adrenal crisis-low blood pressure, vomiting, fainting, even death. You’ll also need to carry an emergency injection of hydrocortisone and wear a medical alert bracelet.

Should my family get tested if I have pheochromocytoma?

Yes. Between 35% and 40% of cases are inherited due to gene mutations like SDHB, SDHD, VHL, or RET. Even if no one else in your family has had symptoms, they could carry the gene. Genetic testing for first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, children) is strongly recommended. Early detection can prevent life-threatening complications before they start.

Comments (15)

Ady Young

November 29, 2025 AT 19:46 PMI had no idea pheochromocytoma could mimic anxiety so perfectly. My cousin was misdiagnosed for five years with panic disorder-turns out her BP was spiking to 220/130 during episodes. She cried when she found out it wasn't 'all in her head.' Surgery fixed everything. No more meds. No more fear.

Travis Freeman

December 1, 2025 AT 10:33 AMThis is the kind of post that makes me believe medicine still has magic in it. A tumor you can’t even feel, but it’s wrecking your life-and then poof, one surgery and you’re back to normal? I’m sharing this with my dad. He’s had ‘stress-induced hypertension’ for 15 years. Maybe he needs this test too. 🙏

Sean Slevin

December 2, 2025 AT 14:28 PMWow. Just... wow. I mean, think about it-your body’s fight-or-flight switch is stuck in the ON position, and nobody knows why? It’s like your autonomic nervous system got hacked by a rogue biological app. And the worst part? Doctors think it’s anxiety because, well, anxiety is the new black diagnosis for everything that doesn’t have a clear label. I’m not even mad-I’m just amazed we’re this far into the 21st century and still missing stuff like this. Also, why isn’t this on every primary care screening checklist? It’s not rare enough to ignore. It’s deadly enough to demand attention.

Chris Taylor

December 4, 2025 AT 13:45 PMMy sister had this. She was 28. They thought it was thyroid issues, then menopause (she wasn’t even 30 yet). She lost 20 pounds in three months and couldn’t sleep. One day she collapsed in the grocery store. The ER doc finally ordered the metanephrine test. Turned out her tumor was the size of a lemon. Surgery was scary, but now she’s back to hiking and cooking and laughing. This post gave me chills. Thank you.

Melissa Michaels

December 4, 2025 AT 19:57 PMThe diagnostic criteria for pheochromocytoma are well established but underutilized. Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with episodic hypertension accompanied by the classic triad. Early biochemical testing with plasma-free metanephrines is both sensitive and specific. Genetic counseling should be offered to all patients regardless of family history due to the high prevalence of hereditary syndromes. Surgical preparation with alpha-blockade is non-negotiable. Failure to adhere to protocol carries significant morbidity and mortality risk.

Nathan Brown

December 5, 2025 AT 20:16 PMIt’s wild how something so small-a tumor the size of a walnut-can hijack your entire nervous system. We treat high blood pressure like it’s a broken faucet, but what if it’s actually a bomb ticking inside you? And we miss it because it doesn’t fit the mold? I think we’re scared of the things we can’t measure. Anxiety? Easy. Tumor? Scary. So we pick the comfortable answer. But sometimes… the uncomfortable answer is the one that saves you. 🤔

Matthew Stanford

December 7, 2025 AT 05:38 AMFor anyone reading this: if your BP won’t stabilize even on three meds, and you get random sweats and heart palpitations-ask for the urine test. Don’t wait. Don’t let them tell you it’s stress. You know your body better than any algorithm. This isn’t a rare disease-it’s a rare diagnosis. You deserve to be heard.

Olivia Currie

December 9, 2025 AT 04:34 AMI’m literally crying right now. My mom had this and no one believed her. She went from being a vibrant yoga teacher to barely able to walk without fainting. They told her she was ‘too young for hypertension’ and ‘just sensitive.’ She almost died during surgery because they didn’t prep her right. I’m so glad this exists. Please, if you’re reading this and feel like your body is betraying you-keep pushing. Find someone who listens. You’re not crazy.

Curtis Ryan

December 9, 2025 AT 10:42 AMSo wait… you’re telling me I could’ve been cured of my ‘high blood pressure’ if I’d just asked for a simple blood test? I’ve been on meds for 8 years. Eight. Years. I’m mad. I’m so mad. 😡 But also… hopeful. Gonna ask my doc next week. Fingers crossed.

Rajiv Vyas

December 10, 2025 AT 18:39 PMThey say it’s a tumor but what if it’s just the government’s new way to control us? Like, what if all these ‘rare tumors’ are just people who got exposed to 5G or fluoridated water? I mean, why would they hide this cure? Because if everyone knew you could fix BP with surgery, the pill companies would go bankrupt. And who profits from that? Exactly.

farhiya jama

December 11, 2025 AT 03:49 AMUgh. Another long post about medical stuff I don’t care about. Can we just talk about TikTok trends instead? This is why I hate health threads.

Astro Service

December 11, 2025 AT 19:15 PMWhy are we letting foreigners run our medical system? In America we don’t need fancy scans and genetic tests. Just take a pill and shut up. This is why our healthcare is so expensive. They’re overtesting everyone. This is just another way to scare people into spending money.

DENIS GOLD

December 13, 2025 AT 01:11 AMOh wow. So the cure is surgery? And you need to take pills for two weeks before? That’s it? That’s the whole thing? No laser beams? No alien tech? Just… a scalpel? I’m disappointed. I thought this was gonna be sci-fi. Guess reality’s just boring now.

Ifeoma Ezeokoli

December 14, 2025 AT 04:53 AMMy cousin in Lagos had this. No access to metanephrine tests. No laparoscopic surgery. She waited three years. She died before they found out. This post? It’s a lifeline. But not everyone has a doctor who knows what to look for. We need this info everywhere-not just in the US. 🌍

Daniel Rod

December 14, 2025 AT 21:04 PMJust read this at 3am. My heart is pounding. Not because of a tumor… but because I finally understand why I’ve felt off for years. I’ve had random sweats, headaches, and my BP spikes when I stand up. I thought I was just ‘anxious.’ But now… I’m scared. And hopeful. I’m booking an appointment tomorrow. Thank you for writing this. ❤️